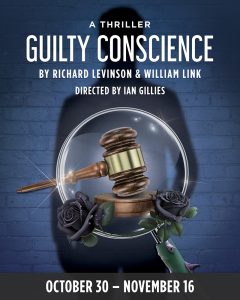

Ian Gillies, who directed the play Guilty Conscience at the Ottawa Little Theatre, poses a question: what does justice look like? Well, it looks like theatre, Mr. Gillies. I attended the matinee this Sunday afternoon of the 1985 play by Richard Levinson and William Link. While billed a suspense, it’s sprinkled generously with light, comic moments.

Arthur, played by David McIntyre, is a confident, clever and corrupt lawyer in New York City. He’s unhappily married to Louise (Melissa Raftis), has an affair with a younger woman called Jackie (Teresita Thorne) and then proceeds to cheat on her as well. Arthur is a charming serial philanderer, he’ll do anything to win a case, he’s abusive, amoral and he’s plotting to murder his wife. By any objective standard, he’s a terrible guy. And yet David McIntyre’s excellent acting and the compelling dialogue make him sort of likeable. He’s got a certain swagger. He wears a three-piece pinstriped suit, smokes cigars, replenishes his drinks and that of his wife from their very 1970s home bar, and wrestles with how to orchestrate his wife’s death — and get away with it.

A wrinkle in his plan is that his long suffering wife comes to plot his demise as well, in collaboration with Arthur’s spunky mistress. Louise demands a divorce alongside an advantageous financial settlement, seeking to be liberated from her loveless marriage. She becomes more determined than ever after he strikes her in the course of an argument. Louise blackmails her husband, threatening to reveal to the District Attorney all his dirty secrets and his long history of professional misconduct. Always underestimating his wife, Arthur can’t process that while he plans her death, she might be plotting his, too.

One of Gillies’ creative innovations is that while Arthur is planning out his defence in his head, his imagination makes him face a female prosecutor, rather than the male appearing in the original play. In fact, there’s a transcendent element to this Ottawa Little Theatre production. Three women dressed as Ladies Justice torment Arthur. They also turn to the theatre audience several times in the play, addressing us directly, treating us something akin to jurors. It effectively drives home the idea that American justice is often theatre, where objective truth may take a backseat to narratives constructed and presented in entertaining ways.

The Ottawa Little Theatre production is on until November 16th. Today’s matinee was a full-house, so if you’re interested in attending, I suggest buying your tickets in advance.

Christopher Adam